Messier 42 - The Great Orion Nebula

A historical perspective on Messier 42, the Great Orion Nebula

Messier 42, also known as the Great Orion Nebula or the Sword of Orion, is most famous nebula in our night sky. It is also one of the few nebulae visible to the naked eye and, for most people in this hobby, the very first nebula they ever photograph. As you may probably already guessed, this was also the first nebula I have ever captured. I captured my first image using my old Omegon Advanced 150/750 telescope, paired with a ZWO ASI224MC planetary camera. This was far from an ideal setup for deep-sky astrophotography, but at the time I was primarily focused on planetary imaging, and deep-sky felt like something I could only dream of pursuing in the future.

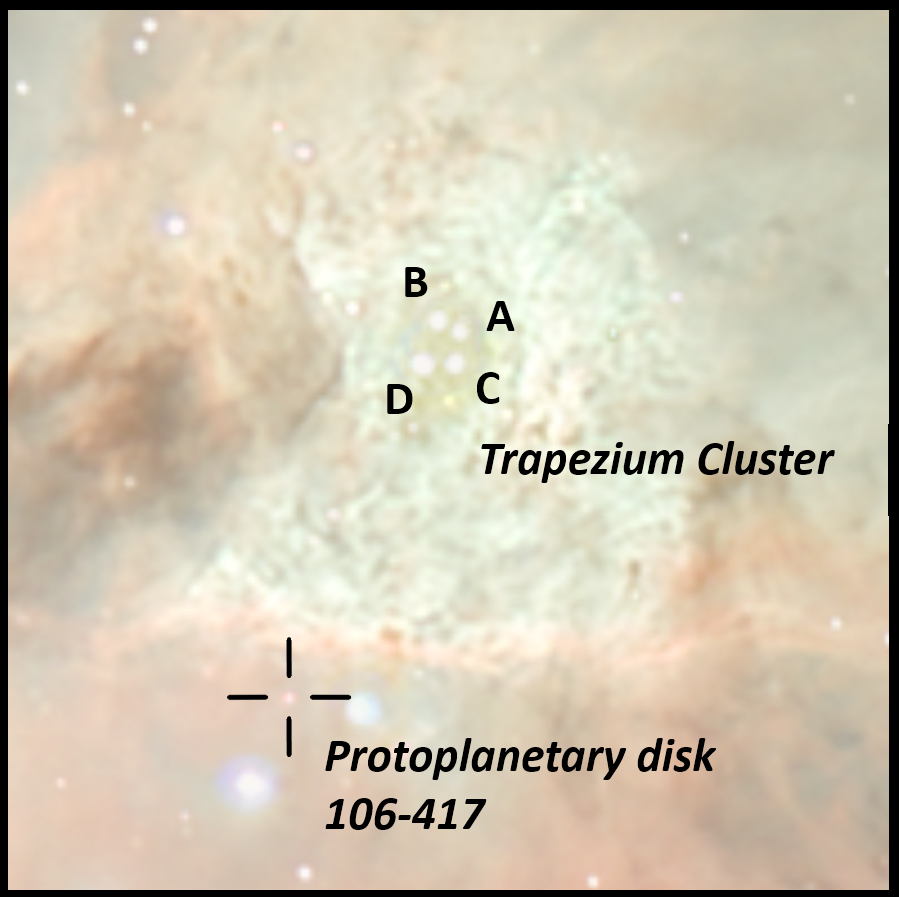

Although my first image of the Orion nebula was nothing extraordinary for a beginner, it did contain something that I was unable to reproduce in the following years, until the image you see above. At the heart of the Orion Nebula lies a young group of stars known as the Trapezium Cluster. The four brightest members of this group are commonly referred to as stars A, B, C, and D. The cluster was first discovered by Galileo Galilei on 4 February 1617, and he was able to resolve three distinct stars in the nebula’s core using one of the earliest telescopes. Considering the limitations of early refractor telescopes, this really was and is an impressive achievement.

What made my first image special was that, due to the relatively long focal length of 750 mm and the short exposure times used for each subframe, the Trapezium Cluster was clearly visible. At the time, I did not fully appreciate how difficult this can be to achieve. In the years that followed, I used several refractor telescopes with shorter focal lengths, which made resolving the individual Trapezium stars more challenging. In particular with my William Optics Redcat 51 MK2.5 telescope, I was unable to distinctly separate stars A, B, C, and D in the core of the nebula.

The Trapezium Cluster & a protoplanetary disk

In stellar terms, the Trapezium Cluster is extremely young. The A, B, C and D stars are estimated to be only 1 million to 3 million years old. For comparison, our sun is approximately 4.6 billion years old. The full designations of these stars are:

- Theta¹ Orionis A

- Theta¹ Orionis B

- Theta¹ Orionis C

- Theta¹ Orionis D

There is also a fainter star, designated as Theta¹ Orionis E, which lies between the A and B stars, However resolving this star requires a level of detail that exceeded the capabilities of my telescope back then. In March of 2025, I purchased a new cooled deep-sky camera, the ZWO ASI2600MC Air. This camera has a smaller pixel size compared to my previous ZWO ASI294MC Pro camera. So maybe I am able to capture additional detail in this region during a future imaging attempt.

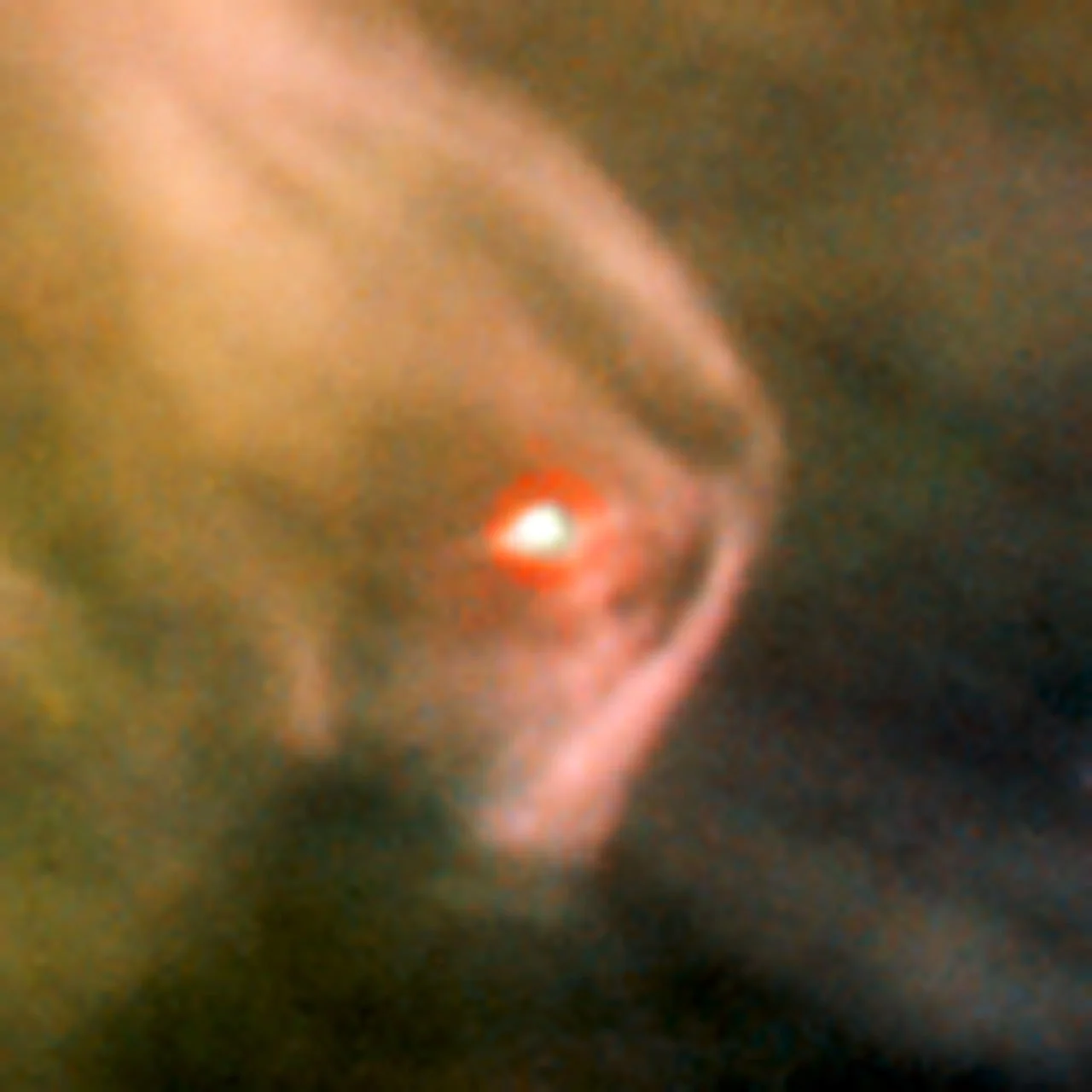

While doing research on Messier 42, I came across a Hubble Space Telescope (HST) image of Orion’s core, showing not one, but six protoplanetary disks within this stellar nursery. After examining the apparent size of these dusty spots, I decided to compare my own image of the nebula’s core with the HST image, to see if there was a small chance that one might be visible. To my surprise, I did indeed find one! Protoplanetary disk 106-417, which can be seen in the up close image in this blog post. Discovering an unexpected object in my own data is always a rewarding experience, and adds an extra layer of scientific depth to each image.

So what exactly is a protoplanetary disk, and why is it remarkable to see one in an image captured by an amateur astrophotographer here on our Earth? the answer is partly revealed in the termijn “proto”, meaning “earliest”. A protoplanetary disk consists of a molecular cloud of gas and dust that is collapsing under its own gravity. As it contracts, it forms a rotating, flattend disk with a newly formed protostar in its center. Disks like these are mostly composed of hydrogen and helium gas, the same elements from where stars are formed.

It is not possible for someone with a normal telescope to obverse the protostar itself, as it is deeply embedded within cold, dense gas. However, the James Web Space Telescope (JWST) can! With its ability to observe in the infrared portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, some that my equipment cannot, it can detect these hidden objects. Infrared photons emitted by the protostar are able to penetrate the thick surrounding material. Making the JWST an extraordinary tool for sudying early stellar evolution.

The protoplanetary disks near the core of the Orion Nebula are estimated to be around 300,000 years old. Slowly but surely the protostar at the center expels lighter gases toward the outer reions of the system, and the remaining dust particilars gradually unite to form planets. Near the inner regions of the disk, rocky planets, simulair to Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars can develop. And the abundant hydrogen and helium gas in the outer regions can give rise to gas giants like Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

In most cases, protoplanetary disks produce powerful jets emerging from the poles of the protostar. These jets form when large amounts of infalling material cannot be fully incorperated in the disk, and are instead ejected along the star’s rotational axis. The process resembles a cosmic whirlpool, with matter spiraling inward while excess material is ejected outward.

My close up of Orion’s core

Protoplanetary disk 106-417 as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope

Messier 43 Mairan’s Nebula

Discovered by Jean-Jacques d’Orteous de Mairan in 1731, and later cataloged by Charles Messier in 1769. The Mairan’s Nebula is a HII emission nebula near Messier 42. It is physically part of the Orion Molecular Cloud Complex, but it received a separate designation because it appears to be distinct from the Orion Nebula, separated by a prominent dark dust lane. The ionization of the hydrogen gas of the nebula is caused by the bright star at the center of it, also known as NU Orionis.

Just like Messier 42, this region also contains young protostars embedded within dusty protoplanetary disks. Sadly I was not able to find these structures in my own image. However, having already identified a protoplanetary disk within the Orion Nebula itself, I wont complain! The Mairan’s Nebula It is often overlooked due to it begin so close to Messier 42 and its slightly fainter apparent magnitude of 9.0. I think is this really impressive when considering that the nebula is mostly ionized by a dingle star.

Normally, I capture Messier 42 every year. However in 2026 I plan to focus on another nebula iwthin the Orion constellation, that being Messier 78. This reflection nebula features some very interesting dark dusty structures and and nearby hydrogon-alpha emission regions, known as “Barnard’s Loop”. fortunately I recently purchased a pair of Celestron Cometron binoculairs with which I am still able to observe Messier 42 up close in 2026.

Messier 43 - Mairan’s Nebula

Acquisition details:

Optolong L-Pro lights:

1hr 30min

36x 180sec

0hr 02min

126x 1sec

Calibration frames for each stack:

20 Darks

20 Flats

20 Biases

Bortle: 5

Gear used:

🔭 Askar 103APO

⚙️ Sky-Watcher EQ6-R Pro

📸 ZWO ASI294MC Pro

🌌 Optolong L-Pro

My previous captures of Messier 42

Messier 42 - The Great Orion Nebula, photographed using my William Optics Redcat 51 MK2.5 telescope and ZWO ASI294MC PRO cooled deep-sky camera

Messier 42 - The Great Orion Nebula, photographed using my Omegon Advanced 150/750 telescope and ZWO ASI294MC PRO cooled deep-sky camera

Messier 42 - The Great Orion Nebula, photographed using my Omegon Advanced 150/750 telescope and ZWO ASI224MC planetary camera. This was the image with the four distinct Trapezium Cluster stars

Messier 42 - The Great Orion Nebula, photographed using my Omegon Advanced 150/750 telescope and ZWO ASI224MC planetary camera